Cabaret is a performance built on dissonance — between pleasure and devastation, seduction and collapse, spectacle and war. Set within the visual and sonic grammar of classic drag and showgirl performance, the piece draws its aesthetic from Liza Minnelli’s Cabaret — sequins, bowler hats, stylized movement, exaggerated eyeliner — but inserts this familiar language into a violently unfamiliar context: the backdrop of war, displacement, and border regimes.

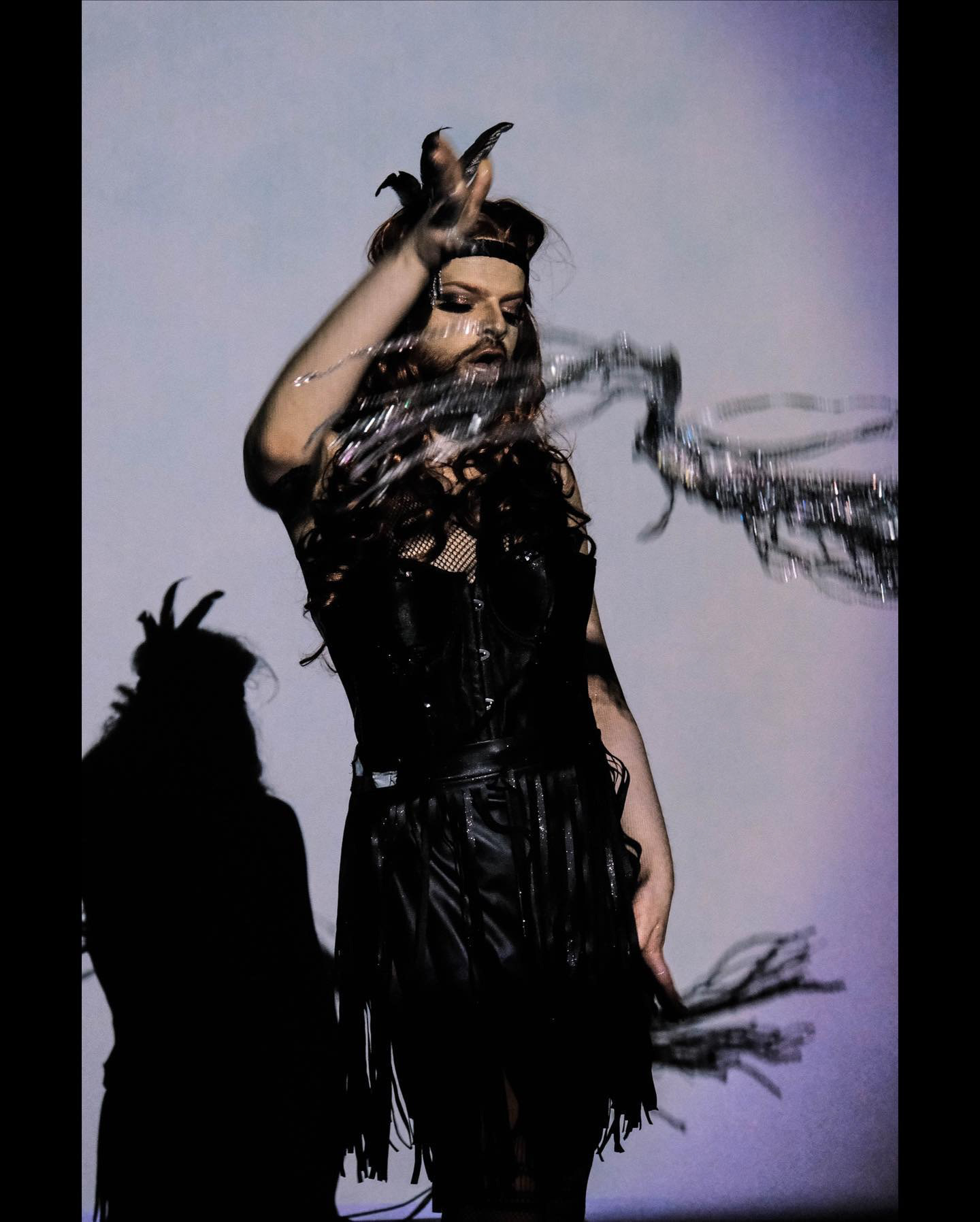

The work doesn’t merely borrow from pop-cultural icons. It disfigures them. It stages beauty in crisis. Here, the glamour of performance doesn’t distract from the brutality of the world — it collides with it.

Projected images and references from contemporary geopolitical conflicts — including the Russian-Ukrainian war, the humanitarian catastrophe at the Polish-Belarusian border, and the racialized policing of migrants and refugees — interrupt the show. They do not appear as background material, but as active agents within the performance’s emotional architecture. The tension between the glimmering body onstage and the horrors offstage is not resolved. It is sharpened, held, exposed.

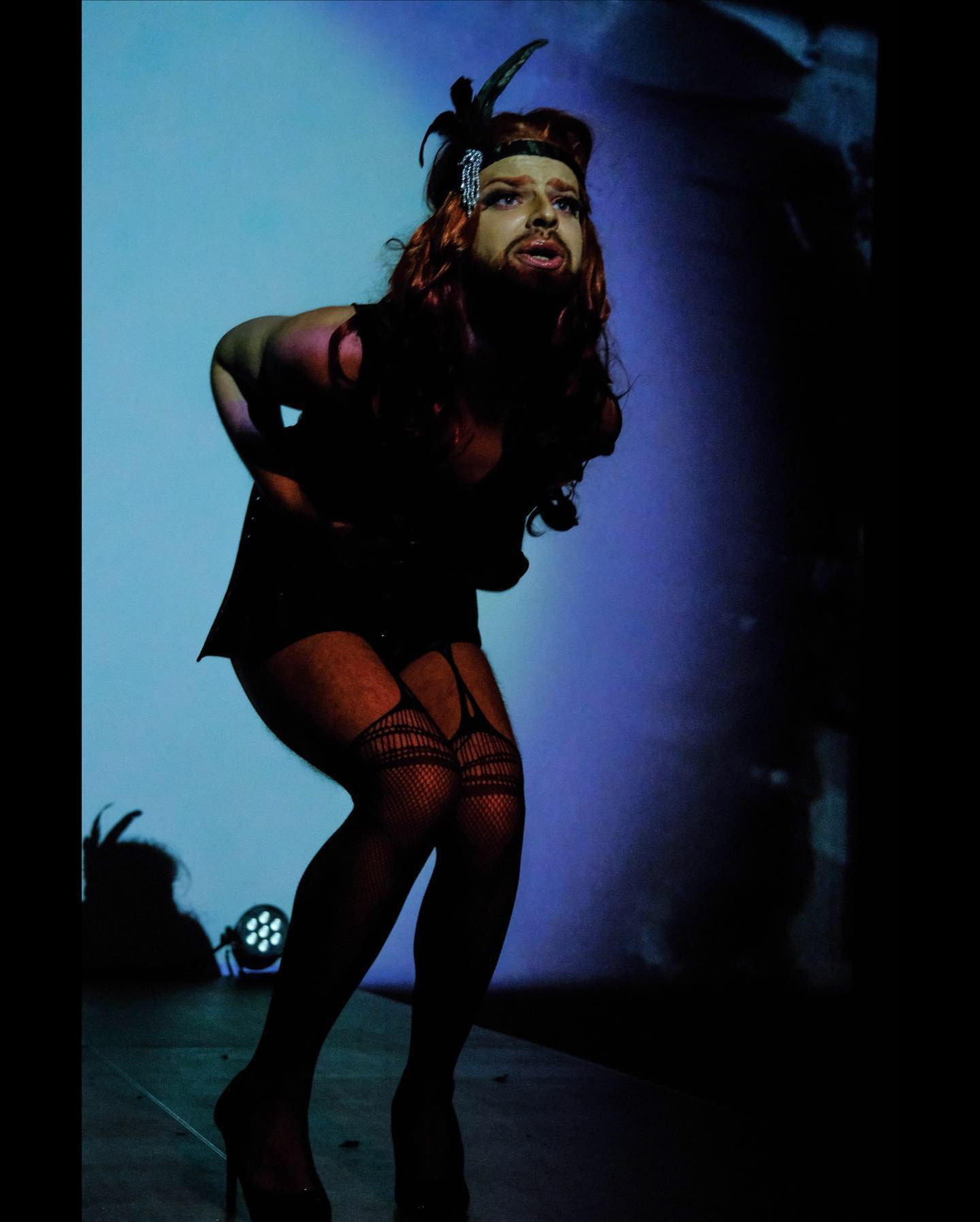

The performer — clad in fishnets, corsetry, and drag hyper-femininity — becomes both object and operator of confrontation. Striptease sequences are carefully choreographed to mirror not only the peeling away of clothing but the political exposure of the world around us. To undress in Cabaret is not to titillate. It is to reveal what is normally kept invisible: trauma, state violence, the spectacle of migration, the sexualized spectacle of suffering.

Chains, harnesses, and BDSM props further complicate the visual economy. Dominance and submission no longer belong solely to the realm of sex — they point instead toward the systems that govern bodies, borders, and mobility. The question becomes: who owns the body, who controls its movement, and what does it mean to perform in a world where the right to exist is constantly negotiated or denied?

In this space, pleasure is not innocent. Neither is glamour. Cabaret does not present suffering and seduction as opposites — instead, it insists on their interdependence. The body onstage becomes a battlefield: a place where joy and horror press against each other, where the language of desire is weaponized, where every gesture carries weight.

The work is punctuated by the phrase: “No to war. No to borders. No person is illegal.” Spoken not as a slogan, but as an embodied refusal. These words rupture the performance’s theatrical surface. They do not ask for consensus — they demand discomfort. They expose the impossibility of political neutrality in a world built on regulated movement, racialized violence, and enforced disappearance.

Cabaret asks what it means to perform femininity, queerness, and visibility in times of war — when spectacle is everywhere, when resistance is co-opted, and when the drag body is simultaneously hyper-visible and politically disposable. It refuses to resolve into hope, tragedy, or uplift. Instead, it lingers in the unbearable proximity of laughter and mourning.

The audience is not left at a safe distance. There is no clean division between witness and voyeur, between the erotic and the ethical. The viewers, too, are caught — in the rhythm, in the tension, in the seduction of a world unraveling before their eyes.

Cabaret offers no catharsis. It’s not here to make you feel better. It’s here to show you what happens when art doesn’t turn away.